Was Dr. Britt Baker vs. Thunder Rosa a breakthrough for AEW? (March 23, 2021)

On My Screen This Week

This issue’s selections continue to be brought to you, for the most part, by a four-year-old having to isolate after a COVID-19 case in his pre-school.

Dr. Britt Baker vs. Thunder Rosa (AEW; March 17, 2021)

A genuinely historic TV main event, the St. Patrick’s Day bout between Dr. Britt Baker and Thunder Rosa found itself faced with numerous questions about both its build and its execution and, rather than attempt to answer them, mostly just fought past with sheer force of will.

To begin with, beyond the fact that they could, there was no logical reason why the promotion offered this up with an unsanctioned stipulation, as the feud had not built anywhere near that level of steam. On television, furthermore, the Lights Out concept really stretches the suspension of disbelief, because after the ceremonial switching of the lights on and off, to signify that the sanctioned part of the show has ended and the unsanctioned begun, here Justin Roberts continued to announce the participants, the usual AEW lighting and music played Baker and Rosa to the ring, and the commentary team stayed in position. To even get close to making a Lights Out bout work logically, none of these things should have been present, and a nice effect would have been for the AEW crew to have begun removing the set as the bout went on.

Problems with the concept notwithstanding, the first action of the bout was for Baker’s second, Rebel, to strike Rosa with a crutch, signifying that the match was not going to have the decisive conclusion that these encounters are designed to achieve.

Early on, after Baker had earned a two-count by hitting a death valley driver onto the staging area, Rosa wildly threw a chair at Baker’s face, and then proceeded to beat her down with it. This too had a deleterious effect on the bout, however, as Rosa repeatedly chose to strike Baker in the back, which was clearly the safest place for her to do so. It’s a good thing that wrestling is aware of the real-life consequences of head trauma, but in a match so apparently hate-filled that it required this stipulation, it made no sense for Rosa to use the weapon in the least harmful way possible. Aside from not using it at all, a simple way to have avoided this logic fail would have been for her to work over a limb to set up a submission hold later on.

It was ironic that when the match was bumped to the picture-in-picture screen that Baker did some of her best playing to the camera, but even taking a break for commercial sponsors was an unintentionally hilarious element of this supposedly unsanctioned affair.

Already bloody herself, the match went full double-juice when Rosa kicked a ladder into the head of Baker, who then visibly reached to her head to blade as the director was overly conspicuous in sticking to very tight shots of her opponent. Sure enough, Baker came up bleeding, and not too long after was the recipient of a brutal death valley driver from the second rope onto a ladder, only for her to kick out on two.

Certainly, Baker took most of the worst punishment, including a powerbomb into thumbtacks after Rebel had earlier retrieved them. The most clever spot of the bout actually came from this, as Rosa made Baker let go of the Lockjaw (modified Rings of Saturn) by rolling her into the tacks.

After Rebel had dragged the match down further by waiting around to be bumped through a ringside tablet, the finish came when Rosa and Baker battled on the ring apron, with Rosa getting just enough of an advantage to hit a co-operative Emerald Frosien through a table onto the floor.

It would be unfair to write this bout off entirely, because the effort put forth was outstanding, and both Baker and Rosa played their individual roles well. Still, the match lacked a basic logic and both failed to convince that there was actual hatred between the participants, and that they were competing to win. (**1/4)

Bret Hart vs. Yokozuna (WWF; April 4, 1993)

Although Yokozuna (real name: Rodney Anoa’i) had been hugely impressive during a run for New Japan Pro Wrestling that went back as far as 1988, it was somewhat of a surprise to find him in the main event of Wrestlemania just six months after his debut in the WWF. For this new top heel role, he had changed his style to be more deliberate and impactful, as opposed to showing off just how much he could do as a super-heavyweight.

Yokozuna, as a gimmick, was never going to rate highly on the five-star scale, but his offence looked brutal, and it was impossible not to have a visceral reaction to some of his best spots, such as a crushing legdrop off the ropes.

Bret Hart was a perfect rival, as their combination offered “The Hitman” the opportunity to come up clever ways to take down his monstrous opponent. Thus, at the beginning of this bout - held in the visually pleasing outdoor arena of Caesar’s Palace - Hart leapt at Yokozuna with a dropkick, and then tied his foot in the ropes so that he could strike with a second-rope elbow.

When Yokozuna took over, it was with believable knockdowns that slowed the pace so that Hart could rebound at the opportune moment. The challenger’s rare bumping was perfectly timed, including one off a turnbuckle shot that sent him to the canvas for Hart to apply the Sharpshooter. This had been a question built for weeks: could Hart apply the hold to someone as big as Yokozuna? The answer was yes - just about - giving the babyface champion a moment of triumph before Mr. Fuji threw salt in his eyes, allowing Yokozuna to capture the pinfall and the WWF title.

What happened in the aftermath is now memorable for the wrong reasons, but Hulk Hogan taking immediate control of the championship was the right move in that moment, and at no other time thereafter. (**)

Hakushi vs. The 1-2-3 Kid (WWF; August 27, 1995)

Having debuted for the WWF against this same opponent in January 1995, seven months later the bloom was off the rose for Hakushi, the elegant aerialist once known as Jinsei Shinzaki in Michinoku Pro Wrestling.

While this Summerslam encounter was still somewhat of a dream match, Hakushi - who had initially worked a TV programme with an impressed Bret Hart - had for the previous six weeks been doing ignominious house show jobs for the likes of Adam Bomb, Savio Vega, and Fatu. The 1-2-3 Kid hadn’t fared much better, over the same period dropping matches to Waylon Mercy (Dan Spivey) and Hunter Hearst Helmsley.

Still, for their 9 minutes here, they showed what they were capable of, competing with a level of skill way above their push.

In between keeping to his methodical gimmick, Hakushi showed his trademark poise with a handspring elbow and a Space Flying Tiger Drop (of the much more difficult backflip variety). When he fired back, the Kid got the crowd of their seats with a big dropkick and a crossbody from the second rope inside the ring, down onto his opponent on the floor, and even hit an early version of the frog splash for a near-fall.

Unfortunately, the bout then ended right as it had picked up, with a modified powerbomb giving the Japanese grappler the pinfall. Still, the pair had offered a glimpse into what could have been a division to rival WCW’s cruiserweights, who would first start to come to prominence on Nitro a month later. (***)

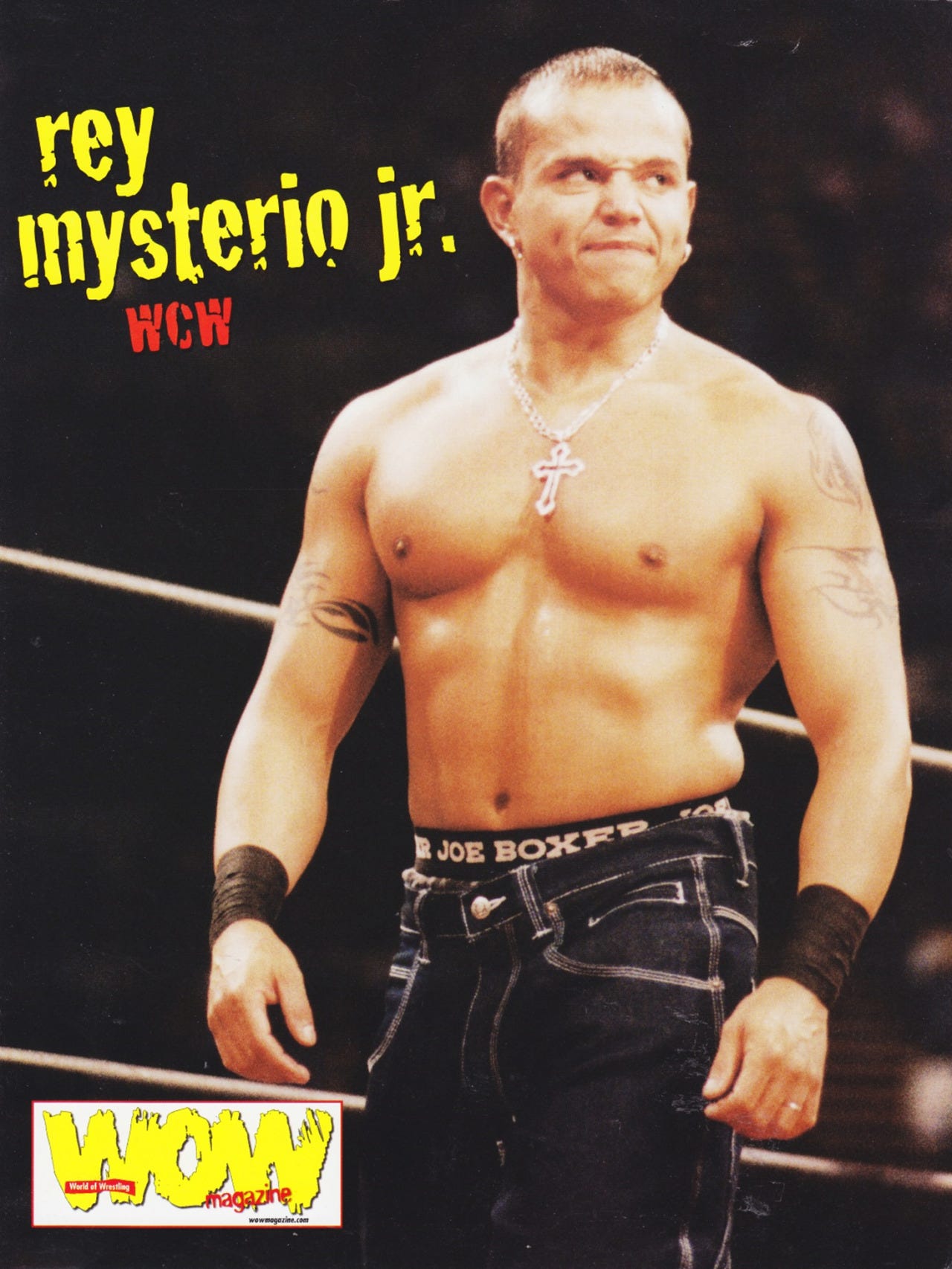

Even given all of the remarkable luchadors on the roster, in 1998-99’s WCW no-one could surpass Billy Kidman for quality cruiserweight contests. While his best series was with Juventud Guerrera, this March 1999 bout with Rey Misterio Jr. was a fantastic 10 minutes of action that exemplified the exhilarating highs of Nitro.

Really, what we were seeing was lucha libre at the next level, with fewer of its foibles, especially as it relates to heel shenanigans. With this being a TV bout, there was little inclination to build up an in-ring story or to work the crowd slowly into the match, so instead Kidman and Misterio went at it hard and fast from the get-go.

There was good contact on almost everything they went for here, including a springboard cannonball splash to the floor by Misterio, and a powerbomb reversal by Kidman that really slammed Misterio’s head into the mat. After 9 minutes of wild, unpredictable action and more ‘ranas than you could count - and, unfortunately, a frustrating ad break - Misterio countered Kidman’s own reversal into a spectacular second-rope bulldog for the three-count.

This bout may have been the very definition of a spotfest, but it worked for the live audience, and not even the most miserly of viewers could argue that this wasn’t thrilling. (****)

Hulk Hogan vs. Roddy Piper (WCW; December 29, 1996)

Michael Buffer, the ring announcer of “Let’s get ready to rumble!” fame, was reportedly getting $5,000 for every single utterance of his catchphrase on WCW television, but had he been worth his cheque he’d have done a lot better than to sarcastically refer to this Starrcade 1996 main event as “the match of the century”.

To give him some credit, the claim was only as absurd as the idea of booking it in the first place. They may only have been 42 and 43 years old respectively, but Piper and Hogan had run the gauntlet of the 1980s, and had the injuries to prove it, the most notable being a right hip Piper had had replaced with titanium a year earlier.

This was never going to be a war to settle the score.

The former WWF rivals always had chemistry, but here Hogan did his best to kill it, and Piper’s chances of upstaging him, by stalling at a time when the bout needed a mean, hard edge. As such, it quickly devolved into an all-too-basic, waking-pace brawl, and even when Piper tried to up the intensity by lashing Hogan with his belt, the reaction was tepid.

Not only was the match fought at half-speed, but it was not the least bit epic, although Piper putting Hogan out with a sleeperhold did send the contest home at its most interesting point, and in an unexpectedly decisive manner. (*1/4)

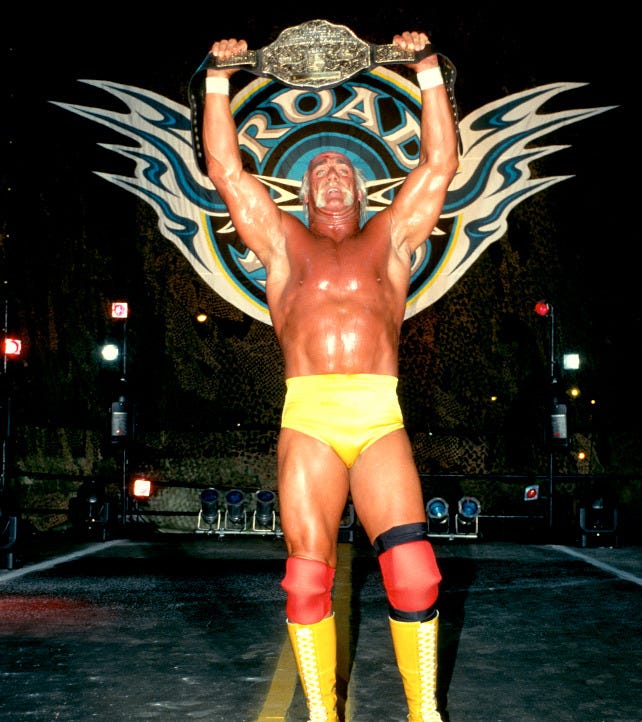

It had been three years since Hulk Hogan last donned his patented red and yellow attire, and the natural venue for him to return to his beloved self was… certainly not Boise, Idaho. Still, three weeks after being beaten up by former nWo cohort Kevin Nash, the classic Hogan emerged for this six-man tag team encounter to the strains of American Made, and an incredible reaction from the live audience.

I suppose that it’s correct to refer to this as nostalgia, even if the gimmick had only been gone for three years, as the reaction largely kept up through Road Wild, when Hogan allegedly sent Nash into retirement. Hogan himself, though, could not keep up the level he reached in this initial bout, where he competed with an intensity that might have kept the run going if he’d physically had it in him.

The heels were in full ‘80s bumping mode here, particularly Sid, who made no effort to hide that he was going along with everything Hogan wanted. This awkwardness rather summed up the bout in quality terms, but this was all about the excitement and adrenaline that Hogan’s babyface return created.

Despite its flaws, it remains one of the most memorable moments in Nitro history. (**)

On My Podcast App This Week:

A thorough and entertaining analysis of the week’s topics from Rich Kraetsch and Joe Lanza, with a particularly frank discussion of new GHC champion Keiji Muto.

John McAdam and John Muse discuss the year 1990 in pro wrestling. Both men were in the thick of the hardcore fan scene at the time, and thus provide a unique perspective on matters of the time.

Not too many podcasts can really get deep on details of Japanese pro wrestling history, but here WH Park and Dylan Fox do just that with regard to one of the greatest wrestlers of all-time, Toshiaki Kawada.

A Little Bit Of Housekeeping

You’ll have to excuse the lack of topical articles in this issue, as we’ve had a COVID positive in our household. Everyone is fine, but some writing time has been lost.

I am available for further editing and occasional writing work, with my credits being for various international newspapers, news agencies, and websites. I also have a decade of editing experience. You can inquire about these, and my rates, by emailing brian(at)hardcopy(dot)ie. I can also provide professional editing feedback, or offer advice or mentoring, by prior agreement and through the same email address.